While Columbia is a globally respected academic center, it is also a vital local New York institution, committed to the economic, intellectual, social, and cultural vitality of our neighborhoods and city. In that spirit, together with our West Harlem neighbors, elected representatives, and civic leaders, Columbia has developed a plan for a mixed-use academic center that provides a long-term future of shared opportunity in the old Manhattanville manufacturing zone of West Harlem.

The New York City Council approved the University's rezoning plan by a wide margin in December 2007, at the conclusion of the city's extensive public land use review procedure. In announcing the vote, the City Council said the plan "preserves and enhances the vitality of the neighboring Harlem community, while providing new research, cultural, and other benefits to the University."

Columbia's comprehensive plan, limited to these blocks, moves away from past ad-hoc growth of University buildings. Gradually over the next quarter-century, this carefully considered, transparent, and predictable plan will create a new kind of urban academic environment that will be woven into the fabric of the surrounding community.

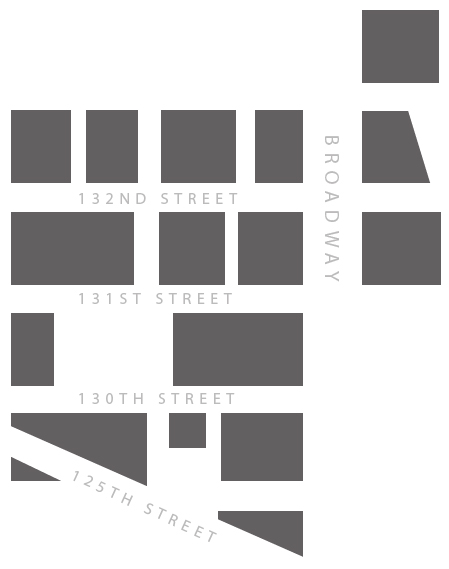

-- Columbia University's Manhattanville in West Harlem Site

Since Columbia announced its plans to build another campus in the Manhattanville section of West Harlem over four years ago, the university has met a great deal of opposition from local residents, business owners, community boards, and members of Columbia's own faculty and student body. While each of those battles -- ranging from Nick Sprayregen and Gurnam Singh's refusal to sell their property to a student-organized hunger strike during November of 2007 -- is central to the narrative of this site, this project does not aim to make an explicit statement about the expansion and its opponents.

Instead, this site is meant to function as a comprehensive archival record of the Manhattanville area -- as it existed at its earliest stages of development and urbanization in the mid- to late-nineteenth century, through its rapid industralization through the early 1900s, and its slow decline toward the second half of the century. By 2030, Manhattanville will undergo one last, presumably final reincarnation into another Columbia campus. This project is an attempt to capture the neighborhood as it appears now, teetering on the cusp of that next great change.

Three hundred years ago, Manhattanville was a largely unpopulated wooded valley. Traces of the area's original topography still linger in the steep descent from Morningside Heights to Manhattanvile, particularly along Amsterdam Avenue from 118th to 125th Streets. In the 1800s, houses began to slowly pepper the valley, largely functioning as farmhouses and churches.

But in roughly the twenty years after the turn of the 20th century, that little dip in West Harlem underwent a series of staggering changes, and by the 1920s Manhattanville was the transit hub of Manhattan. New York's first subway line, then known as the IRT, passed through 125th Street and Broadway with the first elevated subway platform in the world. The just-completed Riverside Drive Viaduct, which managed to navigate the steep dip of Manhattanville by linking Morningside Heights and Hamilton Heights with an elevated overpass, was also considered a revolutionary feat of engineering with its spans frequently crossing a block or more at a time. And the Harlem River Piers -- once Manhattan's only major port on the Hudson -- accepted all incoming traffic and shipments from New England and the continental United States.

As the area became a central location for shipping and transporting throughout the city, however, the neighborhood's businesses changed to reflect that particular industry. By the late 1940s many of the large brick and stone buildings in the area became storage facilities to field all of the incoming goods. Residential life began to peter out as entire apartment buildings were taken over and architecturally reinforced to operate as long-term storage. And as the residents left, smaller businesses decided to vacate the area -- and their spaces, too, were converted to storage.

By the '70s, the rest of New York City had caught up. The MTA had largely built up the subway system, significant ports had been established all along the Hudson River, and Manhattanville -- already stripped of most of its residential culture, was stripped of much of its industry as well. But the storage facilities stayed, and the area became largely comprised of windowless warehouses like Tuck-It-Away Storage with its five buildings scattered from 125th to 134th Street, Despatch Moving & Storage Co. on Broadway and 131st Street, Hudson Moving & Storage Co. on Broadway and 130th Street, and Manhattan Mini Storage on 12th Avenue and 135th Street.

But with the rapid exansion of the Upper West Side and the steady "gentrification" of the Columbia University neighborhood in Morningside Heights, Manhattanville found another function; for cabbies, truck drivers, and commuters Manhattanville was the first place to stop for gas along Broadway for miles, as well as the last place to fuel up before merging onto the Henry Hudson Parkway heading into Westchester. Remaining retail space was quickly consumed by auto body shops, gas stations, and car washes -- as Manhattanville ceased to exist as a transit hub and became something more closely resembling a rest stop.

Most of the images you will find in the "PHOTOS" and "INTERVIEWS" sections are of Manhattanville as it exists today. Columbia now owns or has finalized agreements with the owners of roughly 90% of the real estate from 125th to 133rd, between Broadway and 12th Avenue, with the notable exception of Nick Sprayregen and Gurnam Singh's properties. In the next 20 years, almost exactly a century from Manhattanville's last period of rapid renovation, most of these buildings will have been replaced with Renzo Piano's distinct glass and steel architecture. This site serves as documentation of what once stood in its place.

-----

This site was created by

Daniella Zalcman as part of an independent study during her senior year as an undergraduate architecture major at Columbia University. All photos -- except those credited to Columbia or Arcadia Publishing -- are copyrighted and not for reproduction without permission.